Every now and then, someone sends me one of those social media memes that say something clever like “I am silently judging your grammar” or “I can’t be friends with someone who has typos.”

Usually I smile and say thanks. Sometimes, though, I stop to explain that I’m not that kind of editor. I don’t fix people’s spelling, and I’m not really interested in your dangling participles.

“So, then, what do you do, exactly?”

“I’m a developmental editor.”

And then I get a lot of blank looks.

Most people know that a copy editor goes in and marks up text and fixes grammar. Copy editors and proofreaders correct obvious (and not so obvious) mistakes.** They use those big red pencils. (Well, not really anymore, but Track Changes has the same visual effect.)

Developmental editing is fuzzier. What does a writer actually get out of a dev edit?

Well, a lot, actually.

What Is Developmental Editing?

A developmental editor evaluates, critiques, guides, and helps shape your work while you’re still writing it.

Dev editing is sometimes also called substantive editing, or content editing. Both in substance and style, it can vary widely from one editor to another (this is an area so subjective that we can’t even decide what to call it). So all I can really speak to here is my own approach, which I learned and cobbled together from very smart editors who have gone before me.

I rarely touch the actual words in a manuscript during a developmental edit. (Most dev work is delivered either in a separate memo, or in in-line comments along the side of the manuscript. I (mostly) won’t comment on your spelling or how well you use commas. Instead, I’m looking at bigger questions:

Does this work?

Where does this still need work?

My response might come in a 10-page memo, or 40 pages of chapter-by-chapter notes, or in sidebar comments, or in a phone call.

Every manuscript is different, but here’s an overview of what I’m looking for as a developmental editor:

In fiction/narrative nonfiction (memoir, history, etc):

When I look at a narrative manuscript for the first time, I’m looking at plot (is the conflict clearly communicated, does the reader see “what’s at stake,” do the unfolding events make sense, is the resolution clearly tied to the building scenes, etc.), characterization (are the protagonists and antagonists consistent and believable, do relationships unfold over the course of the novel, are the secondary characters supporting the story without taking it over), setting (do you have something original and well crafted, and does it support your story without taking over), pacing (is the book constantly building a sense of anticipation), and craft and storytelling (is the writing polished and professional, or are there issues that will distract the reader from what you’re trying to share).

I might come back to a novelist and tell them (kindly and gently) that their characters are too bland, or there’s no clear motivation for the protagonist’s behavior, or there’s this “sagging” section in the middle where nothing happens.

In prescriptive or informational nonfiction:

I’m looking first at whether the primary purpose is clearly communicated and broad enough to draw readers in (does the reader immediately see what benefit they will get from reading, or will they recognize their own questions), whether the author demonstrates trustworthiness (what credibility do you bring to the project, and how well do you communicate that with the reader), organization of material (do chapters flow naturally from one point to the next, is there anything that seems to be missing logically), unique perspective, and craft (is the writing polished and professional).

In nonfiction, I might tell a writer that they’re making assumptions about what the reader already knows (and so need to step back and provide more context), or that the manuscript fails to deliver on the major premise or promise, or that the anecdotes are stiff and not yet relatable.

It’s important to say that I don’t fix these things FOR the writer, although I always try to point out a way to address the issue. A developmental editor will talk to you about the work that you, the writer, still need to do.

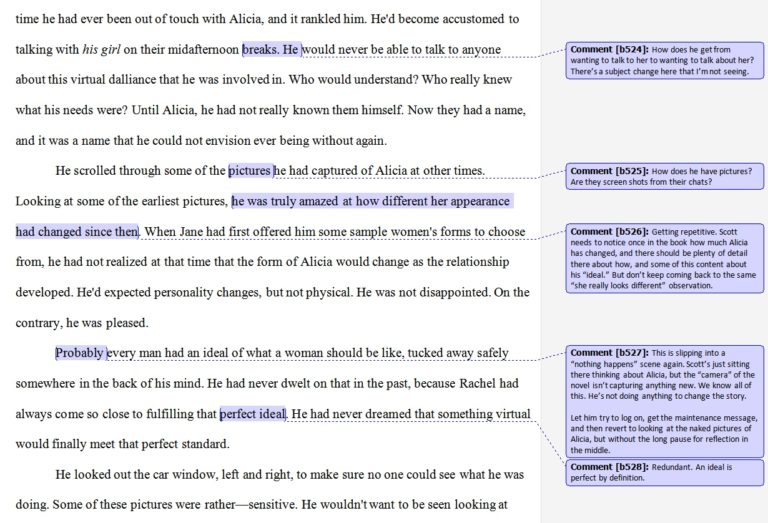

Here, for example, is an actual page of a novel that I worked on a few years ago, which the author bravely shared on his own blog. (It went on to become Friend Me, by John Faubion, published by Simon & Schuster’s Howard Books.)

When Should You Bring in a Developmental Editor?

Hiring a developmental editor is a significant investment (the Editorial Freelancers Association says that the average dev editor charges $45-70/hour), and one that you should approach strategically. You don’t want to pay someone to tell you what you already know. But after you’ve done your own self editing (check out my self-editing checklist here), take stock:

- If this is the first book you’ve ever written, or…

- If you’ve been working on this book for so long that you’re sick of it and think you can’t look at another page, or…

- If something’s bothering you about your draft, but you can’t put your finger on what, or…

- If you’re getting conflicting advice from your critique group or beta readers, or…

- If you’ve been getting rejections from publishers/agents and don’t know why…

…Then you would benefit from a professional review from a developmental editor.

Have you worked with a developmental editor? What was your experience? What did you learn?

**This is a shallow and probably terrible explanation of copy editing. For a more comprehensive look at the different types of editing available, check out these articles from The Northwest Editors Guild and the Editors’ Association of Canada.