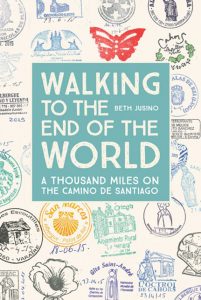

In 2015, I got the urge to write a book. I’d recently returned from a sabbatical in Europe, where my husband Eric and I walked a thousand miles on the Camino de Santiago, a network of pilgrimage trails that date back to the Roman Empire. (You can read more about that on my personal blog, Camino Times Two.) I hadn’t intended to write about the trip when I left, but when I got back I couldn’t shake the suspicion that there was something book-worthy in the experience.

I’d worked in book publishing for almost two decades by that point, including the past seven years as a developmental editor and collaborative writer. I’d seen hundreds of manuscripts, both fiction and nonfiction. And while there was a lot about becoming an author I didn’t know yet, I did know that the first publishing tip wasn’t just to start typing away at Chapter 1.

Instead, I opened a new Scrivener document and wrote four words:

What’s the Big Idea?

In publishing circles, we sometimes call the answer to this the hook, tagline, or, in nonfiction, the subtitle. What it’s called doesn’t matter as much as the clarity of the answer, because wanting to write a book is different than having a book that other people want to read.

Ask the Tough Questions

Let’s face it, readers aren’t lacking for good books these days. Half a million new titles hit the shelves last year alone. For a book to find an audience in this crowded market, it needs something new and fresh that’s clear right from the very first page.

I’d done my homework already, browsing bookstore shelves and Amazon keywords to find out what was already available. I knew my book wouldn’t be the first narrative account of the Camino de Santiago. There were well-respected memoirs from a variety of different voices, including a Catholic priest from Spokane, a German comedian, and the famous spiritualist Shirley MacLaine. There were dozens (and dozens and dozens) of self-published stories from writers of all ages and countries of origin.

Considering that crowded field, before I started writing I needed to spend some time with the same questions I’ve asked of every book I’ve edited:

What is it about this idea that will catch the attention of a total stranger? What will convince them to invest their money and time in this book when they have so many other options?

What is different about the approach this book takes from others like it?

What is the future reader of this book looking for that they can’t find now?

What will they see in the first five pages that will make them keep reading?

That’s what I mean by the Big Idea. It’s not easy for most writers to see their work through the eyes of a stranger, but without that step, we all too often end up losing time chasing an idea without an audience.

Saved by the Big Idea

In fiction, knowing the Big Idea upfront can help writers push past predictable (boring) plots and stock characters, as well as avoid unnecessary tangents and distractions. It can also help them identify strengths and play them up from the very beginning.

In nonfiction, the Big Idea is everything. Readers come to nonfiction books, including memoirs, with two big questions: What’s in this for me, and why should I trust you (the author)? Those are hard questions to answer for a writer who doesn’t already know what they’re trying to do.

As an editor and a collaborator, I help writers stop and understand their Big Idea, which has been a critical part of working with them to tighten, focus, and sometimes radically change their works in progress. If what will draw the reader to a memoir or novel is an incident that happens in a person’s adult life, then all of those early chapters about childhood can be cut. If a self-help book is about building stronger family relationships, then every chapter needs to point back to that goal. The Big Idea defines the structure.

So What Was My Big Idea?

These were the first two sentences I wrote in my brainstorming file:

It’s about the gift of letting go, getting outside, and living at a human pace.

My Big Idea, I realized, was that this was a fish-out-of-water story with a happy ending. I’m not the typical “outdoor travel adventure writer” type. I’m not a risk-taker, and no one would ever mistake me for an athlete. I prefer the comfort of my couch and a good book over . . . well, anything. I’m also not much of a traveler. I’d never been backpacking. I don’t camp. I didn’t speak any French, and my Spanish was atrocious.

And yet I went, and now I wanted to tell my story in order to prove that an outdoor, offline, boundary-stretching adventure is accessible to anyone. I didn’t want this book to dwell on my own moments of emotional change, but to reassure others that they, too, could get off their comfortable couches and do something spectacular.

Stopping to articulate the Big Idea sounds simple, which is why so many writers overlook this critical step. But knowing what set my book apart affected everything that came after it, and those sentences kept me focused over the following months as I wrote my draft, pitched a publisher, and then worked with their editors on revisions. (Yes, even editors need editors.)

If my Big Idea was to write the journey of an outsider, and my goal was to inspire readers toward adventures of their own, that affected my outline—how would I structure chapters to bring the reader on the emotional journey I wanted them to take? It affected my anecdotes and descriptions—which moments illustrated the ideas I most wanted to get across, and which would I need to cut? It affected my voice—should I be formal or informal, funny or serious?

By starting with a single sentence of purpose, I saved myself many months of writing. And hopefully, I created a story that doesn’t just fill my desire to share my experience, but also connects with the people who matter most: the readers.